Brexit: A linguistic Bing Bang?

10 May 2017 /

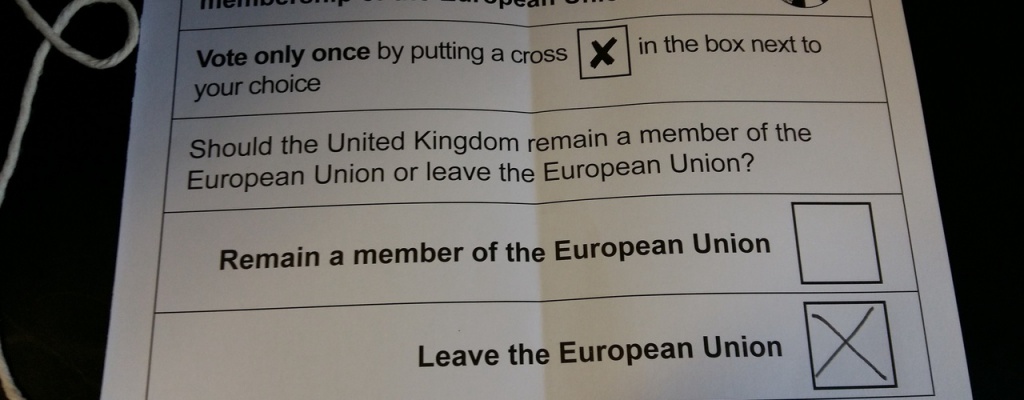

With member States’ and governments’ leaders gathering this weekend to launch the Brexit negotiations’ process, one question is becoming increasingly relevant that of the European Union’s future. With Great Britain leaving the EU, the English could lose its rank of official language within the Union. What then, are the consequences for the institutions, their work and the citizens involved?

Although Malta and Ireland speak mainly English, only Great Britain chose English as its official language within the European Union. Both countries respectively elected Maltese and Gaelic as their official language when they entered the EU. English is undoubtedly the most used language in European institutions and the European bubble. However, due to Brexit, it will be the official language of none of the remaining member States.

The European Lingua Franca

A simple walk through European neighbourhood in Brussels is enough to be persuaded that English is spoken everywhere. Even if each institution has the opportunity to choose its working languages, the English language remains privileged. Since its enlargement in 1995, English has become the first of three official working languages of the European Commission (English, French and German). While in 1997, French and English were almost equivalent – 45% of working papers were published in English, while 40,5% were in French – the gap grew larger over the years. In 2013, 81% of the Commission’s written papers were in English compared to 4,5% in French and 2% in German. At the European Parliament, the outcome is the same. The institution works officially in the 24 official languages of the Union. However, English remains number one. In 2012, English was spoken for 129 hours during plenary sessions, whereas German was only used for 76 hours and French for 38 hours.

A shake-up of the European approach to work

The European Union is the number one employer of translators and interpreters in the world, with approximately 7,000 employees working in these fields. With 24 official languages, there are 526 languages combinations, and not all of them are easy to carry out. In such cases, an intermediate language, called a pivot, is used to switch from the first minor language to the target language. You’ve probably guessed: English is the first language to be used in these cases. Giving up English would have a huge impact for the European Institutions as well as their work and their employees. Their working habits would be shaken, an entirely new set of staff able to work in the other official languages would have to be hired and translation and interpreting services would be disrupted.

The European Union’s work does not only concern its institutions, it also affects thousands of companies that gravitate towards it from within the European Bubble. With almost 20,000 lobbyists and 5,590 interests’ representations, Brussels is in terms of lobbying the second city worldwide, just behind Washington D.C. Exchanges between the institutions and the interest representations (private or public) are almost exclusively done in English.

What about its citizens?

Even though all working documents in the institutions are supposed to be translated into all 24 official languages, this is hardly ever the case. Many web pages from europa.eu are only available in a few languages and sometimes only in English. Withdrawing English from the picture raises the question of European citizens’ access to institutional work. According to a Eurobarometer survey, English is the first foreign language spoken in Europe (for basic knowledge as well as for the ability to understand an article or to have a discussion). English is even the only language from the top 3 foreign languages to be mastered in each of the Member States. No language seems to be able to replace it as efficiently.

Whilst the European Union must face the rise of nationalism and Euroscepticism, should it widen the gap between itself and its citizens by ceasing to use the first foreign language that they learn to speak? At an internal level, during a time when actions are expected on numerous complex subjects, not to use a lingua franca runs the risk of slowing down European progress.

Emmanuel Testenoire for CaféBabel.

Translated by Natacha Lescart.

Article also available on our partner’s website.