International Workers’ Day: How about less work?

09 May 2023 /

Luka Krauss 9 min

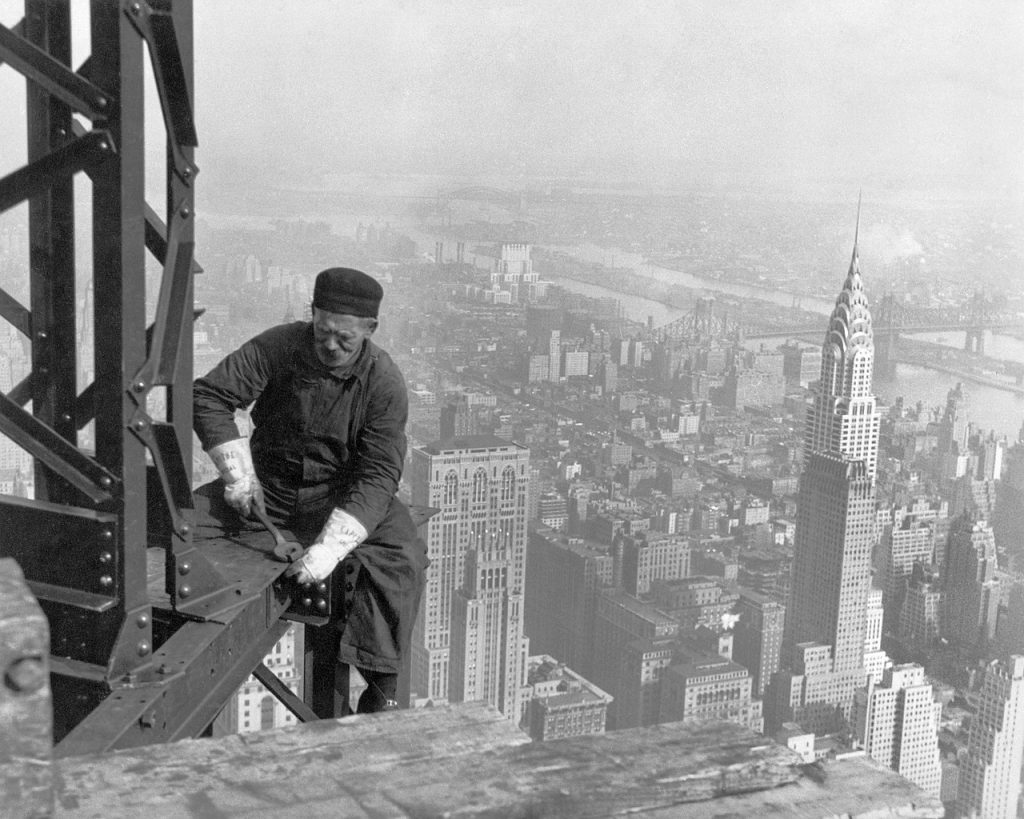

On the 1st of May, several countries across the globe celebrate International worker’s day. The origin of this holiday dates back to the 19th century in the United States. In May of 1886, thousands of workers protested across the country demanding better working conditions. Among other things, they pushed for the eight-hour work day, which is still the norm in most countries today. The protests lasted a few days and led to the deaths of several workers and the explosion of a bomb. The person responsible for the explosion was never caught, yet eight workers were arrested, with seven being sentenced to death. This so-called “Haymarket Affair” became the international symbol for the workers’ struggles, with the 1st of May being chosen as the International Workers’ Day.

Winds of change

“So, what are you going to do after you graduate?”, the infamous question most social science students are confronted with at nearly every family gathering, possibly also on 1st of May. Even though there are still uncertainties about my (and probably your) future career, there is an emerging societal consensus that the role of work in our everyday life will inevitably change in the years to come, although rather gradually than through another “Haymarket Affair”.

The recent pension reform introduced by the French President, Emmanuel Macron could be considered a hint of the upcoming paradigm shift and just one of many manifestations about the dissatisfaction people feel today about employment conditions. The increase of the retirement age from 62 to 64 and the controversial use of article 49.3 of the French Constitution, which allows the passage of a law without the need of parliaments’ approval, brought countless people to protest in numerous French cities.

The increase in the retirement age was justified due to changing demographic trends. This is not unique to France, with populations all over Europe ageing and consequently, people living longer after their retirement. In many Member States, citizens already work longer than in France. In Germany for instance, the retirement age for workers is gradually being increased from 64 to 67. In Italy, people retire around the age of 65. Taking a look at the financial side, France spends around 15% of its GDP to maintain its pension system, while Italy spends more, around 15,8%. Germany only spends around 10,3% of its GDP.

In order to guarantee the financial sustainability of the French pension system and to allow the people protesting nowadays to also receive a pension in the future, the government saw no alternative but to push through the unpopular reform.

While the retirement age and pensions in France are currently hot topics, debates surrounding employment in general are getting more common. Whether it is on the national or European level, improved work-life balance or concepts like the four-day workweek are increasingly present on today’s agenda. Especially concerning the reduction of working hours, supporters hail it as the future of work, ultimately benefiting both sides by increasing work-life balance and employee productivity. Yet, whose responsibility would it be to introduce such changes and who is in charge of labour law in the EU?

A European transformation?

Labour law is a competence shared between the EU and its Member States. While it is mostly in the hands of the latter, the EU, in accordance with article 153 TFEU and and in compliance with the principle of subsidiarity and proportionality, complements policy initiatives taken by the Member States. The EUs Working Time Directive is a central piece of legislation, setting up EU-wide requirements regarding weekly working hour limits, work breaks, paid annual leave, and so forth. Another recent and prominent initiative is the Platform Workers Directive, which is still being negotiated. It seeks to improve the working conditions of people working through digital platforms such as Uber. Over the years, the number of these platform workers has significantly increased, with most of them being self-employed and not able to benefit from the same rights and protection as employed people.

However, going back to the reduction of working hours, the website of the European Commission features a short yet insightful article authored by the European Labour Authority and the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (DG EMPL). Under the category ”Hints & Tips” an article titled “Could a four-day working week be the future for your employees?” gives employers four tips (or hints?) on what benefits they can expect from their employees working a four-day workweek instead of the usual five.

The first benefit is linked to improved productivity, with studies showing that when employees work fewer days, they tend to be more motivated to go to work, giving them extra focus and better time management. Secondly, there is a link with improved mental health and wellbeing, with an extra day off allowing for better recovery and to fully recuperate, reducing illness-related absences overall. Additionally, it would increase employee happiness by allowing them to spend extra time with their family and friends, or doing what they love, possibly boosting their loyalty to the company. And lastly, working one day less would bring positive benefits to the environment. This became evident during the start of the pandemic, with discussions emerging around the flexibility of work and home-office becoming a weekly routine. Hence, when a considerable amount of the workforce started working remotely (for the industries that allowed for it), a strong reduction in air pollution could be observed. Similarly, the reduction of days worked could be argued to have comparable results, with fuel and commuting costs being saved.

While the Commission, with its “Hints & Tips”, is relying on the good will of businesses and Member States, the latter could, if they wished so, make the first move when it comes to the reduction of working hours. They would not have to wait for instructions from Brussels, a quite often used excuse for delaying decision-making in the national sphere. Of course, opinions diverge on the reduction of working hours, which regularly leads to economic and social partners racking their brains over the matter. Moreover, political parties have contrasting opinions regarding the reduction of working hours, with, generally speaking, left-leaning parties being more in favour of the idea and right-leaning parties tending to be against it.

The vanguard of the new work schedule

Looking at some countries who have already taken similar measures, interesting findings can be observed. First, we come back to France. While the country, as has been illustrated above, is today rather in the negative light, it used to be a pioneer concerning working hours. In 2000, France introduced the 35-hour workweek, with the aim of reducing unemployment and improving work-life balance. The “Aubry reforms” were controversial and raised concerns about productivity and economic competitiveness, although studies have shown that it has led to increased job creation and improved work-life balance for employees.

In Germany, trade unions and employers are often calling for reduced working time, despite already having one of the shortest working weeks in Europe averaging around 34,2 hours. Yet, it is still mainly young start-ups implementing progressive reductions of working hours such as the four-day workweek. Meanwhile, the employers’ association of the German car industry pushed for a 42-hour week and pensions at the age of 70, which was even supported by former SPD chairman Sigmar Gabriel.

A success story and pioneer when it comes to the implementation of progressive labour law is Iceland, which implemented a four-day working week and cut their 40-hour weeks down to 35 or 36 hours. The programme was hailed a success, with employees being happier and no losses in productivity reported. The country subsequently began to roll out the four-day workweek nationwide, with around 86% of the workforce having implemented it.

Other examples can be found in Belgium, with a voluntary four-day workweek being introduced, where workers are expected to maintain the same amount of hours over four (longer) days. In Sweden, the implementation of the six-hour workday has been tried with mixed results and the idea still remains politically contentious. In 2021, Spain launched a pilot program for a four-day workweek which will run for three years. Funded by the government with a budget of €50 million, it will allow small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) to take part in the project, with the results possibly being taken into consideration for future policy decisions.

Concerning businesses, the most prominent example is Microsoft Japan, which conducted a month-long experiment in which it introduced a four-day workweek in 2019. The results were astonishing, with a 40% increase in productivity and employees reporting higher job satisfaction and improved work-life balance.

Additionally, NGOs also advocate for a reduction of working hours. For example, 4 Day Week Global is a non-profit organisation that supports a four-day workweek as a means of improving employee well-being, reducing stress and burnout, and increasing productivity. The organisation was launched in 2019 and is part of a broader international movement calling for a shorter workweek.

What do the employees actually want?

A study conducted by 4 Day Week Global about employees that already work a four day workweek showed that 97% of the respondents want to continue with this configuration. While most of them are based in the US and Ireland, similar results could be found on continental Europe, suggesting a significant interest among workers in the EU for a shorter workweek or other forms of flexible working arrangements.

A Forsa survey showed that around 71% of people working in Germany would like to have the option to only work a four-day workweek, with the majority of people in favour of the measure having higher education and being between the ages of 30 and 45. Additionally, ADPs’ Global Workforce View found that around 60% of European workers are keen on the idea of having greater flexibility over when they work, suggesting that ideas such as the four day workweek would be accepted and even welcomed across the Union.

Whereas in the past, a regular eight-hour job allowed for a person to buy a house and provide for a family, this is not the case anymore. With the momentum picking up around the concept of the four-day workweek or a reduction of working hours due to initiatives of progressive Member States, businesses, or interest groups, policy makers should not close their eyes and miss the signs of the times. It is becoming more and more evident that there are things more important to life than work, and everybody should be able and have the possibility to choose their priorities. Whether it is spending time with family or friends, pursuing a hobby, or simply doing nothing for a day. With personal growth and holistic well-being becoming more central to many people than focusing on their career, our affluent societies would do good to acknowledge the upcoming changes.

Therefore, if at the next family gathering someone comments something along the lines of “your generation does not work like mine did”, one might have to concede this time, yet what is wrong with this way of thinking? As such, this should not prevent the younger generations from advocating for a reduction in working hours, in order to guarantee a more harmonious life-work balance.