The new Western Balkans strategy – changing the carrot and no stick diet? (Part 2)

19 February 2018 /

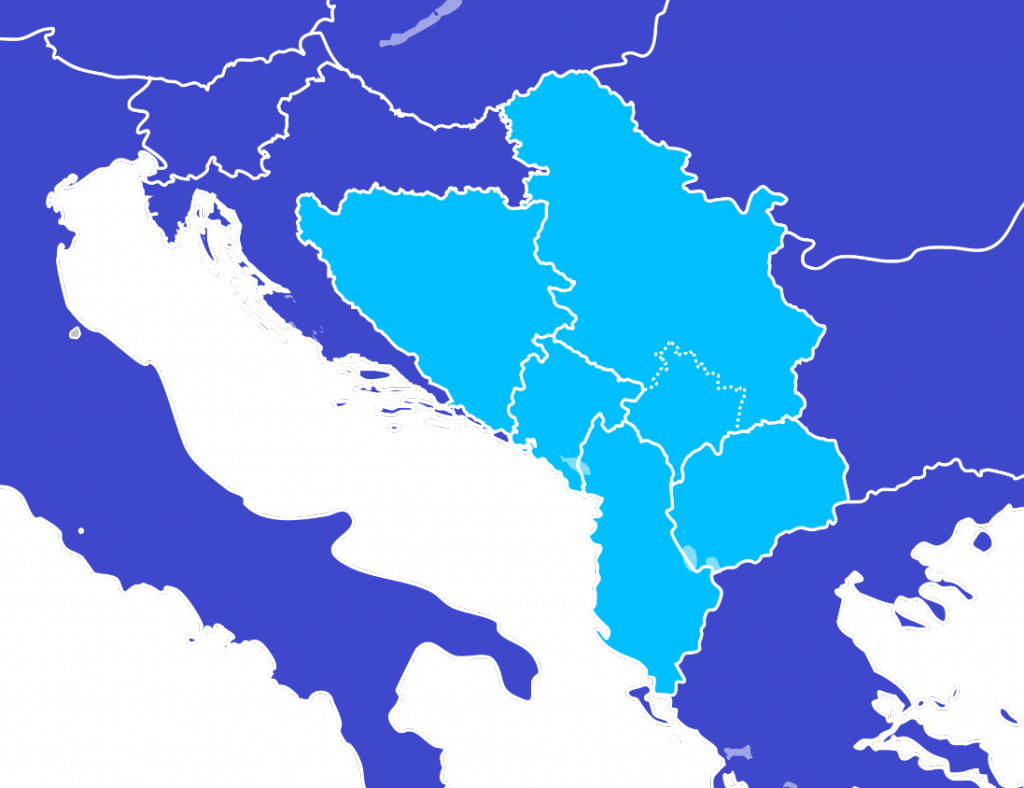

This article elaborates on the mechanics of enlargement in the Western Balkans and deliberates on the extent to which the European Commission’s new strategy on enlargement addresses the past misgivings of the region’s European integration. Its main argument is that while the new strategy on the Western Balkans introduces novel elements into the enlargement process, its success will depend on 1) the swift resolution of bilateral disputes; 2) the elaboration of transitional arrangements that address the fears of EU citizens; 3) the implication of the European Parliament (EP) in the enlargement process; and 4) the reduction of electoral abstention throughout the region.

On February 6, the European Commission announced its new strategy on Western Balkan enlargement. This article builds on the previous one published by Eyes on Europe, which depicts the key elements of the Commission’s strategy and can be accessed here.

Why was the new enlargement strategy necessary?

Enlargement is often depicted through the “carrots and sticks” metaphor. However, as portrayed in the following lines, its status was closer to that of rotten carrots and no sticks months before the release of the new strategy of the Commission.

Reinjecting credibility into enlargement

To begin with, the expiry date of the carrot (think of the membership perspective offered to the Western Balkan states) was past because all relevant EU actors did not express a clear commitment to enlargement throughout the recent crises period.

The President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker did so by insisting that the EU would not enlarge throughout his mandate, and by renaming the enlargement portfolio to “European Neighborhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations.”

Bilateral disputes between member states and candidates effectively blocked and sometimes even reversed the accession process. In the case of Macedonia, the name dispute with Greece, precluded it from starting accession negotiations as early as 2009. This created fertile soil for the autocratic government of Nikola Gruevski that eventually descended into nationalism.

The enlargement perspective of the Western Balkans was further damaged by the political groups within the European Parliament (EP) which often formed their positions vis-à-vis the governments of candidate member states on the basis of partisanship. This was demonstrated during Macedonia’s political crisis when EP members (MEPs) from the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) each took the sides of their partisan counterparts in Macedonia, VMRO-DPNE and respectively SDSM.

European citizens also grew skeptical of the widening of the Union in the midst of an overall enlargement fatigue and numerous other crises. Opinion polls unfavorable of enlargement and the vote of Dutch citizens against the EU-Ukraine association treaty clearly demonstrated this.

Thus, the ambivalent support for enlargement expressed by EU institutions stained the credibility of the membership perspective of the Western Balkans. Henceforth, governments in the region lost an incentive (or won an excuse to lose an incentive) to pursue important reforms.

A stick which does not stick

Besides the withholding of the carrot (which was slowly rotting), the reluctance of the EU to make use of its stick and sanction non-compliance with reforms, for example in the judiciary, also decreased.

Truly, the EU was less critical towards governments in the Western Balkans due to a fear of open confrontation that might create internal political vacuums and/or shatter the fragile stability in the region. On the other hand, the EU was predisposed to tolerate the candidate states’ non-compliance with key reforms since it faced increasing competition in the region from China, the Gulf states, Turkey, Russia and the US.

The considerations mentioned above were, or seem to have been, apprehended by the region’s ruling class composed out of stabilocrats – “autocratically minded leaders, who govern through informal, patronage networks and claim to provide pro-Western stability in the region” (BiEPAG, 2017).

Stabilocrats managed to transmute the lack of overt opposition from the EU by positioning themselves behind the EU on geopolitical matters (for example the refugee crisis in the case of Serbia and the Ukrainian conflict in the case of Montenegro). Preserving stability in the midst of a crises-dominated period allowed them to canvass EU support and slowly advance the enlargement of their states, which in turn improved their reputation at the national level.

Hence, in the months before the new strategy of the European Commission, the carrots and sticks mechanics of enlargement had suffered blows which rendered it inefficient in stimulating reform in important sectors. The ambiguous voices of EU institutions and citizens damaged the credibility of enlargement and constituted an excuse for EU governments not to conduct reforms. Moreover, the latter became less necessarily once stabilocrats discovered they could advance the enlargement process of their countries without committing to reforms by simply maintaining “stability”.

How credible is the new enlargement perspective?

To answer if the new Commission strategy remedies past misgivings of the enlargement process one has to consider the extent to which it reinforces the credibility of the region’s membership perspective and counters the stabilitocratic strategy.

Making credible the incredible?

The effect of the Commission’s new strategy on the credibility of the enlargement perspective yields positive signals. It reaffirms the enlargement prospect of the Western Balkans. For the first time the Commission has given an indicative accession timeline for two states, Serbia and Montenegro, which could be potentially ready for membership by 2025. Nevertheless, even if the Commission has positioned itself as a facilitator of enlargement, the latter will depend also on the actions of other relevant EU actors – the Council, European citizens and the EP.

With regards, to the Council, in the short-to-mid-term it looks like Western Balkan enlargement will remain a relevant topic. This is attested by the statements of Bulgaria, Austria and Romania, the ongoing and upcoming presidencies of the Council, which are in favor of enlargement. Nonetheless, to project a full approval of a meritocratic enlargement, bilateral disputes between member states and candidates need to be resolved as quickly as possible.

At this point the dispute between Greece and Macedonia remains unresolved and there are other potential conflicts on the horizon similar to the border dispute between Croatia and Slovenia, for example the one between Croatia and Serbia. The reinjection of credibility into enlargement will depend to a large extent on the successful resolution of these disputes and in particular the one between Greece and Macedonia, whose non-resolution could strike an early blow to the Commission’s strategy.

Furthermore, whilst citizens in Central and Eastern Europe are likely to rally or at least not manifest against enlargement, the political class in states like the Netherlands, France and Germany could expect to be confronted with a more concerned electorate. In this context, as it is suggested by the Commission, the Council needs to agree on transitional arrangements, for example with regards to the movement of workers, and enforce them upon the accession of the Western Balkan states.

Citizens could also shape the behavior of the EP as the parliamentary elections in 2019 draw near. While MEPs from mainstream political groups recently made favorable remarks about enlargement, the behavior of candidate MEPs might differ if Eurosceptic parties campaign successfully against the accession of the Western Balkans to the EU. Furthermore, MEPs need to ensure that they support enlargement based on meritocracy and not partisanship since the latter could stain the enlargement perspective of the region.

Thus, while the new strategy certifies the support of the Commission for enlargement, the credibility of the membership perspective of the Western Balkans will also depend on the approval of the Council, the EP and European citizens. The bilateral disputes between member states and candidates have a “make or break” potential and especially the dispute between Macedonia and Greece needs to be solved as swiftly as possible in order to produce an atmosphere of positive momentum. Moreover, the EP needs to act as a unified institution and must be prepared to address the fears of EU citizens together with the Council.

Can the EU upkeep a meritocratic enlargement process?

Rather than relying on coercion upon non-compliance with key reforms, the new strategy of the Commission stresses the fact that enlargement is not a “technical process” but a “generational choice.” The Western Balkan states need to address challenges such as the “clear elements of state capture,” the lack of a “functioning market economy” whilst taking “full ownership” of “regional cooperation, good neighborly relations and reconciliation.”

If interpreted together with the expressed clear perspective for enlargement, this new approach implies a meritocratic enlargement based on the conduction of reforms ahead of accession. Nevertheless, the EU should try to stimulate the renewal of the political scene in the Western Balkans because stabilocrats might shy away from reforms. A diminished commitment to reform will be even more likely if the Council and/or European citizens block the process of enlargement at some point.

As it was showcased, the stabilocratic strategy is particularly successful when the EU is confronted with internal crises and external competition from the likes of China, the Gulf states, Turkey, Russia and the US. Thus, if the current economic recovery in Europe backslides or other crises resurface the EU will face a tougher challenge in maintaining a meritocratic enlargement.

Furthermore, even if the political and economic climate in Europe remain stable, as time progresses the stabilocratic elite in the Western Balkans will continue to solidify its power base and this could lead to three possible scenarios.

One is political upheaval like the one observed against the regime of Gruevski in Macedonia, which blocked the reform process in the country throughout two years. The second one is a confrontation with stabilocrats which might create anti-EU sentiments in the region and/or internal political vacuums. The third one is a premature enlargement and an importation of instability.

The EU needs to ensure that it does not become a victim of either of the three scenarios. Therefore, while the strategy indicates that it aims to affect the political process in the Western Balkans by ameliorating the EU’s presence and strategic communication, there are additional measures which can be envisaged.

The first one is the more direct implication of the EP in the enlargement process. The EP is a political institution and the discourse and actions of the MEPs are not subject to the same restraints as those of the Commission and the Council. Politicians in the Western Balkans appreciate the contact with MEPs since these encounters underline and legitimize their “Europeanness.”

Political groups in the EP, or at least the centrist ones, need to take advantage of this and undertake concerted actions to socialize with their partisan counterparts, whilst preserving the meritocratic tenants of enlargement. This could contribute to the renewal of the programs and discourse of some parties in the region which often address the reforms demanded by the EU only superficially.

Consequently, when Western Balkan parties implement reforms, MEPs could use their reputation to legitimize reform-minded politicians. Conversely, EP groups could distance themselves from their partisan counterparts when the latter do not implement key reforms as a form of sanction to stabilitocracy.

Secondly, the EU needs to address non-voting in the region. Approximately half of the voting-age population in the Western Balkans does not vote.

On the one hand, this stains the democratic process as a whole and is likely to be imported on the EU level, upon the accession of these countries. As a result, the Western Balkan region will solidify its place as a latecomer that not only does not add ideas to the European debate but will also further discredit the already discredited EP elections.

On the other hand, non-voting in the Western Balkans severely impairs political competition in the region. The durable rule of stabilocrats relies on abstention as much as on clientelism. A lot of people in the region believe their abstention punishes corruption. However, abstention decreases political competition in the region and increases the weight of loyalist and clientelist votes on which the elite forms its electoral base, thereby perpetuating corruption.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the new enlargement introduces elements that move away from the carrots and sticks mechanics of enlargement that had become largely dysfunctional. Nevertheless, in order to increase the chances of a meritocratic enlargement the new strategy must be complemented by: 1) the swift resolution of bilateral disputes between member states and candidates (notably the one between Greece and Macedonia); 2) the elaboration of transitional arrangements that alleviate the fears of EU citizens in domains such as the movement of workers; 3) the implication of the EP into enlargement as an institution rather than a partisan actor; 4) the increasing participation of Western Balkan citizens in the democratic process.

Venelin Bochev is a Master student in Political Science at the ULB.

Bibliography

Crisis of Democracy in the Western Balkans: Authoritarianism and EU stabilitocracy. Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (BiEPAG), March 2017. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.biepag.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/BIEPAG-The-Crisis-of-Democracy-in-the-Western-Balkans.-Authoritarianism-and-EU-Stabilitocracy-web.pdf.

European Commission. Serbia 2016 Report. Brussels, 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2016/20161109_report_serbia.pdf.

European Commission. A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-credible-enlargement-perspective-western-balkans_en.pdf

Kmezic, Marko. “EU Western Balkans Strategy: On Named and Unnamed Elephants in the Room.” Accessed February 16, 2017, http://www.biepag.eu/2018/02/08/eu-western-balkans-strategy-on-named-and-unnamed-elephants-in-the-room/.

Transparency International. Corruption Perception Index (2016). Accessed November 1, 2017. https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016.