Understanding the Palm Oil War

11 May 2017 /

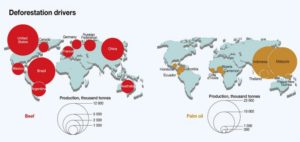

Palm Oil is a highly controversial topic in the Western World and mostly linked to deforestation, CO2 Emissions and Orang Utans, that the EU tries to address. Indonesian people and producers of palm oil however associate it with an unjust EU Policy, in place to protect their own interests and markets from the cheap liquid lubricate.

Nowadays people tend to associate Palm Oil with the destruction of the rainforest in Indonesia and Malaysia. Long before the Europeans started using Palm oil and NGOs started campaigning against it, people were trading the highly productive oil, which was home in the belt of West Africa from Angola to the Ivory Coast.

It was around the year 1849 that the Dutch and the British came up with the idea of importing the seeds of the palm oil tree from West Africa to their respective colony in Indonesia and Malaysia, where it took about 60 more years until it was first sold commercially. The second half of the 19th century was the time when the Dutch, British and French imported many products to their colonies in Southeast-Asia. The Palm Oil trees were growing perfectly in the tropical climate.

“Palm Oil is one the oldest trading commodities in human history.”

When Malaysia was founded as in independent state, the government was developing programs to extend the production of palm oil and supersede the cultivation of natural gummi and timber (Euler, Schwarze, Siregar & Qaim 2016). Since then, Malaysia’s much larger neighbour Indonesia, has overtaken the former British colony and has become the world’s largest Palm Oil producer. Indonesia’s largest customer of Palm Oil products has been the EU for the past years; which also happens to negotiate a free trade agreement with Indonesia at the moment. One of the major points of contentions within the negotiations is the renewable energy directive, which also has an impact on further palm oil imports from Indonesia.

Palm Oil Imports and the Ecological Footprint

Palm Oil can be used to produce biomass. The Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC) of 2009 introduced minimum amounts of renewable energy that must be integrated in the energy household of each Member States and also lays down sustainability criteria for the renewable energy. In 2015, the directive was amended to reduce indirect land use change for biofuels and bioliquids ((EU)2015/1513), which basically tries to prevent the conversion of food crops into energy producing crops. A specific ban on palm oil is not included in the directive but the sustainability criteria indirectly forbids the use of it, with far-reaching consequences for Indonesian Palm Oil imports: the EU is the world’s biggest Biofuel-consumer (European Commission 2017). Making it a large potential market for the cheap tropical oil and the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia is putting a lot of pressure on its government to support further exports. And the Indonesian government desperately needs more exports to reach the economic growth target of 7%.

Many Indonesian individuals suspect that the aforementioned directive is nothing more but an attempt of the EU to protect their markets from Indonesian imports. The widespread narrative in Indonesia even goes as far as evoking that NGOs, like Greenpeace, defamed Indonesian Palm Oil, that they are in cahoots with the EU:

Defending Indonesian Palm Oil

The Indonesian academic Shofwan Al-Banna Choiruzzad conducted several interviews with NGOs, politicians and representatives of the Palm Oil Industry on the origins of the palm oil narrative in Indonesia. He argues that the Palm Oil Industry has created a war trade narrative as a defence mechanism against Greenpeace defamation of Indonesian Palm Oil.

Gapki (Gabungan Pengusaha Kelapa Sawit Indonesia), the Indonesian Palm Oil Association, published numbers that demonstrate how the market share of palm oil has marginalised US soybean oil and EU sunflower and rapeseed oil since the 1980s and these numbers are indeed correct. Further they out forward the argument that the American Soybean Association in the US has already managed to influence the US government in the past. In the 80s they spread the narrative that palm oil has severe impacts on human health and therefore must be forbidden. This led the US Food and Drug Administration to printing warnings on products containing palm oil (Al-Banna Choiruzzard 2016).

“green NGOs have constantly attacked the sustainability campaign, either motivated by real concern about environmental damage or influenced by lobbyists funded by EU and United States vegetable oil producers who are afraid of the palm oil competitive advantage.” Jakarta Post (2017, April 12)

In 2011 Gapki ended its membership of the roundtable on sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and strengthened its ties with the Indonesian ministry for agriculture. When the US Environmental Protection Agency under the Obama administration equally excluded palm oil as a source for biofuels, Gapki saw further evidence for their theory. Gapki started organising workshops for journalists and students on Java and Kalimantan to convince people. On their events, they also demonstrated that Palm Oil needs less land to produce more oil and is therefore much more environmental friendly. Yet, they forgot to mention the problem that comes along when fields are being prepared for palm oil growth: the highly controversial consequences of slashing and burning of the rain forest. Most of the tropical rain forests nutrients are not in the soil, but in the plants. If a piece of land has been grubbed by fire, it will be nutrient by the ashes of the plants for a few years, as the ashes still contain the nutrients of the burned plants. After a short time however, the nutrients are gone, and the previously intact ecosystem is disturbed. The soil itself cannot make up for this loss, and the regeneration of the rain forest is therefore no longer possible, which also renders it no longer usable for agricultural use. Further effects are immense forest fires. Without being industrialized Indonesia has been haunted by these fires, and it gets worse and worse. Indonesia is importantly contributing to spewing more CO2 into the atmosphere, through large amounts of stored carbon which are released from the trees and then mixes with oxygen.

The situation is entrenched, as a great majority still believes that the effects are not serious and the EU is not the best entity to tell Indonesians what to do. Especially because the EU is still seen as a divided body, with little power. Maybe more importantly: haunted by its colonial past and its own climate sins gives the EU little credibility to tell Indonesia moral lessons. Measures like sustainability criteria seem to be the only possible answer, but Indonesia is already looking for new outlets for palm oil, and South Africa, India and China are happy to buy them.

Camille Nessel is a 2nd year MA student at the IEE.