Women’s rights: a multi-speed European Union?

09 August 2017 /

Despite all the measures launched by the European Union in favour of gender equality, the EU Member States do not seem on the same wavelength when it comes to women’s rights.

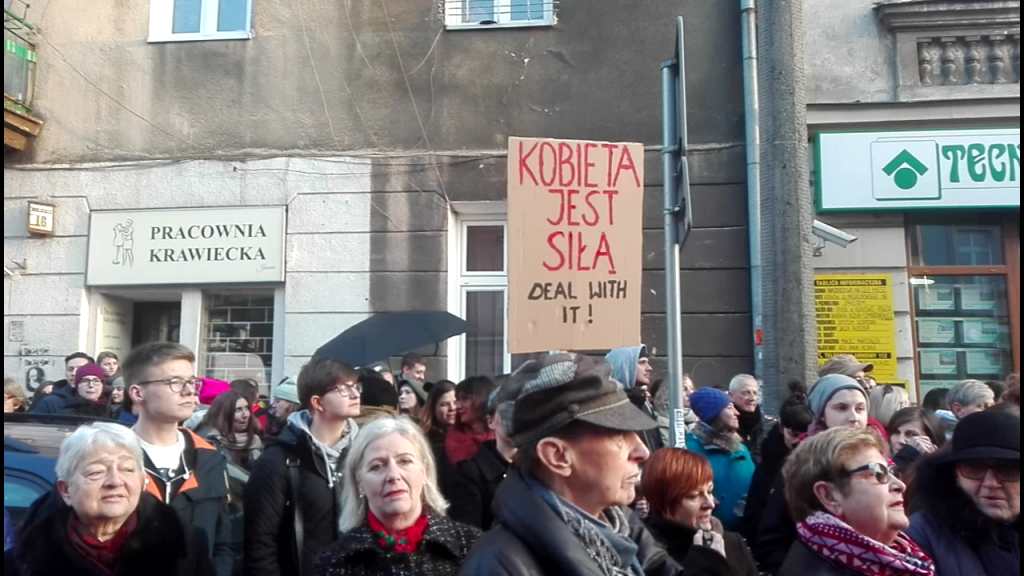

Italy is thinking about menstrual leave whereas Poland is about to debate on abortion (again)

Is it possible to think about the European Union without thinking of it as a community of values? This seems difficult as the European Community has been built on the principles of peace and prosperity and states that would like to integrate the European Union should respect these values. However, gender equality has also been one of the founding principles of the European Community to a certain extent, especially when it comes to the field of employment as it can be seen in Art.119 of the Treaty of Rome. Then, in the Treaty of Amsterdam,the principle of gendermainstreaming has been accepted, meaning that “differences between women and men in terms of conditions, situations and needs must be taken in account automatically in all the policies and measures launched by the European Union” (Ramot, 2006, p.46). But is it working in practice? Unfortunately, efforts towards gender equality have been applied at a slow pace but most of all, they have been applied in a very different way in function of the interpretation of every member state. Thus, whereas in Italy, politicians are thinking about creating a menstrual leave allowing women to have 3 days free per month, their Polish counterparts are trying to make the abortion forbidden by passing a new law in September despite the previous black protests organised by civil society.

Is gendermainstreaming inefficient ?

Being aware of these differences among the member states, should we believe that gendermainstreaming is not working and more generally that the policies launched by the European Union regarding gender equality are inefficient? We could think so, by looking at the case of Iceland for example, which is not a country belonging to the European Union, and which has been the first country in the world to create a law that forces companies of at least 25 employees to prove that they are providing equal pay. In the same way, when it comes to menstrual leave, countries like South Korea, Taiwan or Japan are already applying it. Does it mean that the European Union is not doing anything for gender equality? Not exactly. In fact, to understand why the European Union has limited impact on the gender equality policies of the member states, it is necessary to underline that the field of gender equality is a part of shared competences between the member states and the European Union. These policies are dependent on the subsidiarity principle. Consequently, when the European Union makes suggestions in this field, they are regarded as a part of “soft law” and not as a part of “hard law”. It means that they do not have a binding nature.

Should we make of gender equality, an exclusive competence of the European Union?

Once again, the answer here is more complicated than a simple yes or no. First, there is a need to underline the impact of the interpretation of the expression “gender equality”: one must contextualise every gender equality issue, as it is obvious that through 28 countries, this issue can be perceived differently so that answers to it can be different because they need to be adapted to these various realities. Moreover, giving exclusive competence to the European Union in this field could be a false good idea. Indeed, to require the same practices from all the member states could certainly help to improve gender equality policies in some countries but on the other side, it could also limit the ambitious projects of others, such as Nordic countries, that are already very pro-active. Thus, the European Union supports the achievement of gender equality by suggesting common principles and common structures to implement them but the ones to hold responsible for it remain the member states. In other words, and as it has been said by the philosopher Geneviève Fraisse, “the European Union is more feminist than all of its member states” (Kaci,2013).

Alexia Fafara is studying for a Double Degree Programme in European Studies at Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland and the Institute of Political Studies in Strasbourg, France.